In 1900, Loveland’s electric power system traces its origins to the turn of the 20th century, when Lee Kelim, a young man from Missouri who aimed to revolutionize the city’s energy infrastructure. After arriving in Loveland in 1890, Kelim purchased the Big Thompson Milling and Elevator Co. and expanded its capacity to generate electricity, selling surplus power to the city. As a result, Kelim’s home became the first in Loveland to be illuminated by electric light.

By 1905, as Loveland’s population grew, local merchants began demanding “day currents” — 24-hour electricity. Kelim’s small operation could no longer meet the increasing demand, so he sold his power system to a larger utility company serving the broader Denver region.

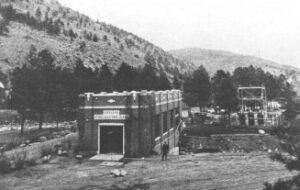

Loveland First Power Station 1925

In 1913, the desire for Loveland to have its own independent power source remained strong, spearheaded by a group of local citizens including upholsterer and strong advocate Chas Viestenz, who proposed building a hydroelectric plant on the Big Thompson River. Viestenz championed the idea of Loveland having its own power company. However, the plan faced fierce opposition from the start. Meanwhile, Loveland was experiencing explosive growth. With legal challenges mounting, it took more than a decade before the project was completed.

On February 11, 1925, the Loveland Light and Power Plant was born, bringing electricity to the city for the first time. Reflecting on the effort, Viestenz later wrote that, after the plant’s completion, he and others involved were in desperate need of rest. “I did not have a shingle over my head that I could call my own. Everything we ever had was gone, including my health,” he admitted. Despite these sacrifices, he took great pride in what the community had accomplished.

In 1973, the Platte River Power Authority (PRPA) was formed when Loveland and three other cities recognized the need for a regional entity to manage the power demands of municipal electric systems. At its inception, PRPA’s peak load was 106 megawatts, and plans were already underway for the Rawhide coal-powered plant, which would begin generating power in 1983.

In 1976, one of the worst natural disasters in Colorado’s history, the Big Thompson River flooded after heavy rainfall, rising from 300 cubic feet per second to more than 31,000 cubic feet per second. The flood destroyed the hydroelectric plant and much of the concrete dam, claiming 139 lives and causing $16 million in property damage. Using federal disaster funds, a new, more efficient power plant was built outside the floodplain, and a flood-resistant dam was constructed. While the new plant only provided 2% of Loveland’s electricity, it did so without polluting the environment.

In 1986, the City of Loveland and the Thompson School District pooled resources to build the Loveland Light and Power Service Center, providing storage for vehicles, maintenance facilities and space for the growing staff, which had expanded to 54 employees.

In 2013, the Big Thompson River flooded again, causing more than $4 billion in damages and permanently putting the hydroelectric facility out of commission. To replace the lost power infrastructure, a 3.5 MW solar facility was built using FEMA funds, adding to Loveland’s renewable energy portfolio and enhancing the city’s resilience to future disasters.

Ushering in a new era of sustainability and clean energy in 2020, Loveland and PRPA have focused on achieving carbon neutrality. In 2020, the Platte River Board approved an Integrated Resource Plan to meet these goals, which includes the construction of new wind and solar plants, as well as the planned closure of coal facilities.

Today, Loveland’s Water and Power Department celebrates 100 years of providing affordable, reliable electricity to over 35,000 homes and businesses across a 74-mile area. As a nonprofit, public power utility, Loveland reinvests ratepayer dollars to maintain high-quality services. In 2025, the City completed its transition to smart metering system because it replaces manually-read electric meters, modernizing the power grid. From its origins as a local mill to its commitment to renewable energy and carbon neutrality, Loveland’s power journey reflects the City’s resilience and dedication to a sustainable future.